| |

|

ENVIRONMENTAL LESSONS

of the

MALIBU LAGOON PROJECT

A Review of the Record

E.D. Michael

March 11, 2014

|

INTRODUCTION

This review of the Malibu Lagoon

project is presented as an object lesson illustrating how an ostensibly well-planned

environmental project can fail despite engendering from its inception

widespread community approval, ratification of various public agencies mandated

to protect or improve the environment, and technical assurances of feasibility.

First, it analyzes the record

concerning, successively, the project in terms of its prehistoric and historic antecedents,

the environmental milieu from which it was conceived, its

planning and approval, its construction, and its performance, each followed by

comments adding to or modifying that record. Second, it discusses the extent to which the project has failed and the

reasons for it. And third, it offers

recommendations regarding how failures of similar projects might be avoided.

MALIBU LAGOON PROJECT

PURPOSE AND RATIONALE

The announced purpose of the Malibu lagoon project was

to "restore" and "enhance" part of the mouth of Malibu Creek, widely

regarded as an oceanic coastal lagoon. The creek mouth on its western side had been modified by grading probably

for agricultural purposes late in the 19th century, covered with artificial

fill during the late 1920s while under private ownership, and after coming

under the control of the California Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR),

regraded in 1983 with channels on the assumption that this would result in

restoring lagoonal conditions and desirable natural habitats. The present lagoon project was undertaken to replace

the 1983 channels with others intended to increase circulation thereby greatly

reducing or eliminating hypoxia and generally improving habitat

conditions.

SCOPE OF REVIEW

This review concerns only

physical aspects of the project It

remains for others to address its ramifications regarding: [i] its asserted

relation to the area's natural ecologic character, especially in terms of so-called

endangered species; [ii] its recreational aspects; [iii] the legality of its

environmental approval; and [iv] an accounting of funds, all far beyond the abilities of this poor

scrivener. Nevertheless, even without attention to such weighty matters, the

subject requires a rather lengthy treatment. Hence, it is presented here in six serial installments. These are: Part I - Floodplain Prehistoric Conditions;

Part II - Lagoon Project Site History; Part III - Environmental Planning and Approval;

Part IV - Lagoon Project Construction; Part V - Lagoon Project Performance;

Part VI - Conclusions Although for some

readers the serial format can be frustrating, I make no apology. If it was good enough for Sir Arthur Conan

Doyle, Henry James, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Herman Melville, it's good

enough for me.

Part I - FLOODPLAIN PREHISTORIC CONDITIONS

The Malibu Lagoon project lies at

the south-easternmost part of the Malibu Creek floodplain. The character of the project cannot be fully

understood without reference to the floodplain itself and the prehistoric period

during which it developed.

ANTECEDENT CONDITIONS

Malibu Creek passes entirely

through the Santa Monica Mountains as a superposed

stream, i.e., a stream that has

maintained its course during a change in the conditions with which it

originally was in equilibrium In this

respect, it is unique in California. The rise of the Santa Monica Mountains block is believed to have begun about a million years before the present (ybp)

during the Pleistocene Epoch considered to have begun about 2.6 million

ybp Then, much of the area from which

the block began its rise had become an erosional surface of low relief and to some

extent an emerged Late Tertiary sea bed. A small part of it was drained by ancestral Malibu Creek - a stream that

meandered to the ocean through an area that now includes Thousands Oaks, Calabasas,

Agoura Hills, and part of the Simi Hills. The rise was so slow that the creek was able to maintain and deepen its meandering

course through the rising block As the

block rose, the creek was rejuvenated so that erosion of its thalweg kept pace

with increasing elevation Once shallow

meanders eventually became the deep gorges now called Goat Buttes and at what

is now Serra Retreat In that process,

ancestral Malibu Creek lost forever the meander-forming mechanism of

stream-bank cutting and filling. Downstream from the Serra Retreat meander, it

can only be assumed that similar conditions prevailed. In effect, ancestral Malibu Creek became a youthful

stream in response to the steepening mountain block gradient while retaining

its old-age configuration to the Pleistocene shore some distance, perhaps a

mile or more, farther south than today.

Comment

This condition should have

prevailed until the beginning of the Wisconsin

glacial episode about 85,000 ybp at which time lowering sea level added

additional energy to that due to tectonic uplift. It is inferred that the lowering sea level

infused the reach of ancestral Malibu Creek closest to the shore with energy

sufficient to introduce locally consequent stream erosion. It is postulated that in the 73,500 years following

the beginning of Wisconsin glaciation the area

from some point downstream of the Serra Retreat meander was transformed to a

youthful terrain Similarly, elsewhere along

the Pleistocene Malibu shore, consequent streams developed ancestral to the master

streams of today from Topanga Canyon west to Little Sycamore

Canyon.

FLOODPLAIN DEVELOPMENT

Beginning about 19,000 ybp, the Wisconsin glacial episode began to wane and sea level

world-wide began rising due to glacier melting. The resulting landward advance of the sea,

called the "Flandrian transgression"

caused shoreline streams to begin aggrading.

In particular, it is inferred that ancestral Malibu Creek in very late Pleistocene

time began this process of aggradation, and that by about 11.5 thousand ybp, at

the beginning of the interglacial episode called the Holocene Epoch, it was

well advanced Since then - with

possible retrograde periods when local tectonic and/or isostatic increments of

rise briefly offset sea-level rise - aggradation has continued. Most important for present purposes, this

model postulates that the present extent and shape of the Malibu Creek floodplain

is entirely in response to the processes of stream clogging and lateral

planation that invariably accompanies stream aggradation.

Certainly within the first half

of the Holocene Epoch and possibly as early as latest Pleistocene time, flow from ancestral Malibu

Creek entered the floodplain from the lowermost reach of the superposed Serra

Retreat meander along which Mariposa de Oro in the Serra Retreat area now is located

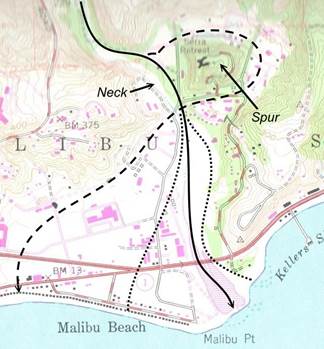

as shown in Figure 1. From near what is now the

|

|

|

Figure 1. Malibu Creek Holocene Floodplain Stream Regimes.

Dashed and solid lines approximate earlier

and later creek regimes, respectively. Dotted lines indicate the approximate predevelopment boundaries of the

later creek floodplain "Spur"

and "Neck" refer to the basic structural characteristics of the Serra

Retreat meander. Base: U.S.G.S. 7.5-minute

Malibu Beach quadrangle, ed. 1981, as modified.

Cross Creek bridge,

just west of the intersection of Mariposa de Oro and Cross Creek Road, the creek flowed on to

the aggrading floodplain in a southerly direction along the base of the Malibu

Knolls slope and past the mouth of Winter Canyon to the shore near

what is now the western end of the Malibu Colony. Probably as late as 1945, the mouth of that

stream, blocked by a barrier sand bar, was a body of water that at least as

early as 1916 was called "Malibu Lake." Probably it persisted into the early 1940's. A remnant of that feature exists today some

500 to 1,000 feet west of Stuart Ranch Road and just north of the massive highway

fill as the only true natural wetland in the Malibu Creek floodplain -

excavated depressions in the entirely artificial Legacy Park notwithstanding.

Probably in

the latter half of the Holocene Epoch - say 3,000 or 4,000 ybp - ancestral

Malibu Creek broke through the neck of the Serra Retreat meander in a manner

yet to be understood The resulting isolated spur became the

promontory that one day Frederick Rindge (1892, p. 70) was to call

"Wunderschön

Vista Ridge" and now is the site of Serra Retreat. As a result, Malibu Creek abandoned its southwesterly

reach in favor of a direct southerly one. Probably, that event did not change significantly the position of the

shore which extended then from Vaquero Point on which the Adamson House now is

located to near what is now the western end of the Malibu Colony. Figure 1 illustrates these two stream regimes

and their geomorphic origins. It is to be understood that although both

occurred in Holocene time, the Serra Retreat meander itself is essentially a superposed

Pleistocene feature Although modified

to some extent by Holocene stream erosion, it required many thousands of years

prior to the Holocene to broaden and deepen it to its basic configuration.

Comment

It is

necessary for present purposes to rationalize the available subsurface floodplain

data from Bausch, et al. (op.cit.) with what has come to be known

as the "UCLA study" by Ambrose and Orme (2000) which, inter alia, interprets the Malibu Creek

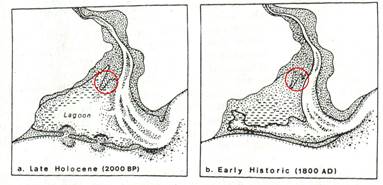

floodplain during the past 2,000 years as having been mostly a lagoon. Accordingly, (op. cit, pp. 2-1 - 2-2), Figure 2-1a of Figure 2 represents conditions

about 2,000 ybp.

|

|

|

Figure 2. UCLA Study Figure 2-1a, b).

Short

dashed lines presumably indicate finer-grained lagoonal deposits and dotted

areas coarser-grained floodplain deposits. The red circles have been added to indicate the general location of the

"Sycamore Grove" - see note (2) below.

To better

understand this interpretation, the following quotation (op. cit., p. 2-2) is cited to which has been added numerals for subsequent discussion:

"... The present estuarine lagoon came

into existence towards the end of the Flandrian transgression culminating in a

reduced but continuing rise of relative sea level of about 1.8 mm per year

during late Holocene and, as revealed by tide-gauge records since 1933,

historic times A reconstruction of the

late Holocene estuarine lagoon some 2,000 years ago, based on field investigations

and comparable analogs (1), is presented in Figure

2-a At the time, Malibu Creek spilled

from its bedrock narrows upon to a fan delta, at time flooding the entire apex,

at other times incising its own deposits to leave a floodplain terrace which

survives above the inner margins of the lowland, subject to inundation during

unusually high magnitude floods (2). Farther downstream, the creek meandered through its estuarine lagoon (3),

but was pushed eastward by the onshore and downdrift construction of a low

barrier beach (4). The greater part of

the lagoon to the west (5) gradually, if erratically,

filled with backwater sediment, occasionally flood deposits, colluvium and

alluvial fan deposits from the adjacent hill slopes, and flood-tidal deltas and

overwash through and across the still incomplete barrier beach (6). With a larger tidal prism than today, channels

through the barrier were maintained for a while by outflowing lagoon waters and

the consequent formation of ebb-tidal deltas (7)."

(1)

- By "field investigations" presumably is meant, primarily, the work

of Bausch, et al. (op. cit.), supplemented by three borings

for the UCLA study, but whether by "analog" is meant: [i] coastal

floodplain depositional conditions elsewhere, or [ii] the presumption of a

similar earlier climatic cycle, or both, is uncertain. However, the idea that up until about 200

years ago there had been a period of at

least 1,800 years during which there prevailed the low-energy stream condition

that a floodplain-wide lagoonal condition requires, is directly controverted by

the available evidence, as discussed below.

(2)

- If by "floodplain terrace" is meant the surface of deposits exposed

after flooding, there are two in the

vicinity of the Malibu Creek floodplain. One is at its eastern edge where a mass of alluvium traversed by Serra Road is

deposited on a coastal platform at about elevation +80 feet msl carved in the

Trancas Formation as mapped by Yerkes and Campbell (1980). Flooding of that area clearly has not occurred

during historic time The other is uncertain

since the surface at the floodplain's northwestern edge at about +25 feet msl

descends more or less uniformly to the northern edge of the barrier bar which,

except where breached, defines the southern edge of the floodplain. The earlier

stream regime of Figure 1 seems to have been ignored in the UCLA study and

suggests that Figures 2-1a and 2-1b of Figure 2, instant, were intended to be

essentially diagrammatic. It is to be noted, however, that the protrusion

encircled in Figure 2 corresponds to a relatively coarse mass of floodplain

alluvium which supports tree growth that Frederick Rindge (1898, pp. 73 - 85)

unreservedly admired and enjoyed which he called "The Sycamore

Grove."

(3)

- There is no evidence of a meandering stream channel in the Malibu Creek floodplain,

and the term "estuarine lagoon" in geologic parlance is a non sequitur. An "estuary" is a partly enclosed

relatively deep coastal inlet such as a fjord freely open to the sea. Its use to describe a coastal lagoon which is

essentially a landlocked feature tributary to the sea only through one or more

shallow tidal channels is to be discouraged.

(4)

- It is important to understand that the eastward-shifting of the channel

breach in the shoreline barrier bar is not "pushed," which implies a

direct application of some sort of force. Rather it is the result of the interaction of: [i] more or less

continual clogging at the mouth of the breaching channel at its western side,

with [ii] east-moving littoral drift, and [iii] the breaching channel flow

rate This mechanism is entirely

independent of the pattern of flow upstream.

(5) -

As previously discussed, the idea of lagoonal

conditions over most of the Malibu Creek floodplain in the late Holocene - or at any time - is simply

speculation The western side of the

floodplain was carved by erosion and lateral planation of the southwesterly

directed stream regime There is no evidence

that the western side of the floodplain was essentially a

lowland subject to filling in late Holocene time.

(6) - The idea of a "still

incomplete barrier beach" in late Holocene time is inconsistent with the existence

of the postulated widespread lagoon shown in Figure 2-1a, the mere presence of

which would require a well developed barrier bar. Barrier bars along the Malibu coast are essentially a function of

wave approach and stream deposits at the shore. They are quite common and well- developed at the mouths of the Arroyo

Sequit, Trancas Canyon, Zuma Canyon, Corral Canyon, and Topanga Canyon. There is no evidence upon which to postulate an incipient condition of

barrier bar formation at the mouth of Malibu Creek 2,000 ybp. Such bar formation is a result of stream

aggradation and wave approach along the Malibu coast - a condition that began to develop with advent of the Flandrian transgression

and persists today

(7) -

The record does not support the

idea of a "larger tidal prism" by which presumably is meant a larger

volume of lagoonal waters in Holocene time up to 1800 AD as Figure 2-1a of

Figure 1 requires Observations such as

this and "ebb-tidal deltas" seem to have no purpose other than to

support a postulated floodplain-wide lagoonal condition which

in the absence of any evidence whatsoever is simply speculative.

FLOODPLAIN SUBSURFACE CONDITIONS

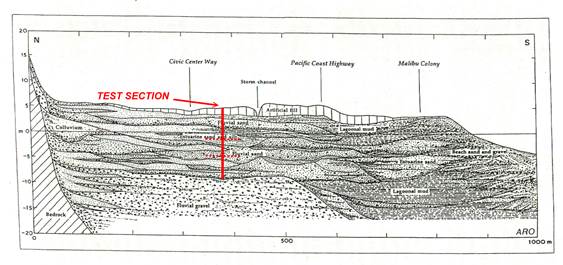

Figure 3 reproduces

Figure 1-8 of Ambrose and Orme (2000, p. 1-16) for the UCLA study. Apparently, it is based largely on data from Bausch,

et al. (op. cit., App. B and C) which include the logs of cores from six

borings and data from two lines of cone penetrometer tests (CPTs). Their data were supplemented by three additional

core logs obtained as part of the UCLA study effort. It is to be noted that the investigation by Bausch, et al.

(op, cit.) was for the purpose of determining the extent to which

conditions such as faulting, foundation-bearing capacity, and liquefaction

might affect development rather than to investigate lagoonal or other environmental

conditions.

|

|

|

Figure 3.UCLA Study Figure 1-8, Modified.

This figure is a generalized north-south

cross-section through the Malibu Creek floodplain from Anthony and Orme (2000,

Fig. 1-8, p. 1-16). "Fluvial

gravel" apparently is the "Civic Center gravels" as

discussed by Bausch, et al. (1994). The dotted lines in the TEST SECTION bracket

a radio-carbon dated interval of 6,500 - 7,850, ybp. Vertical exaggeration:

10X.

Generally, CPT

data describe mechanical conditions. They do not provide any direct lithologic information and have value for

inferring such only if related to lithologic logs from nearby borings. Of the six cores obtained by Bausch,

et al. (op. cit., App B) which range in depth from 43.5 to 55 feet, only

LB-4 encountered organic materials that might be indicative of a lagoonal

environment, and it was located at the abandoned mouth of the earlier Holocene

stream regime shown in Figure 1 This,

and data derived from three cores obtained specifically for the UCLA study,

apparently provide the only basis for its Figure 1-8, reproduced here as Figure

3 Detailed discussion of these latter

three cores (Ambrose and Orme, 2000, pp., 1-15 - 1-20) is essentially an

interpretation of alternating fluvial and organic-rich deposits in the range of

-1.5 to - 47.7 feet msl supported by reports of scattered plant remains

consistent with both fresh and brackish water conditions, and ranging in age

from 1,660 - 9,470 ybp From these data,

the opinion is offered that they are consistent with Figure 1-8 of Figure 3 as

well as another in an east-west direction not reproduced herein.

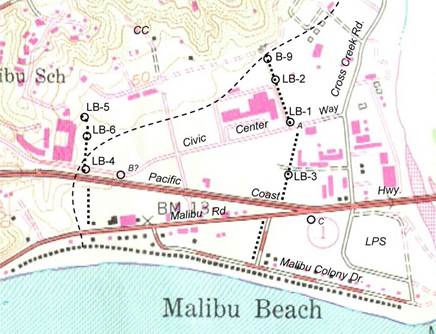

The general

locations of relevant data sites regarding subsurface investigations in the

Malibu Creek floodplain are shown in Figure 4. Bausch, et al. (op. cit., p. 21) note that from boring

B-9 in the "Knapp-Marlin" property, GeoSoils collected two charcoal

samples between depths 19.0 and 19.5 feet and 25.0 and 26.5 feet that yielded

radiocarbon dates of 6,500 ±130

ybp and 7,850 ±100 ybp,

respectively. Although not entirely

clear, it appears from Bausch, et al.

(op. cit., Pl. 1) that the elevation

of the B-9 boring site is at about +23 feet msl.

|

|

|

Figure 4.Subsurface Data Sites - Malibu Creek Floodplain.

LB borings 1 through 6 and GeoSoils boring

B-9 are discussed by Bausch, et al. (op. cit., Pl. 1). The dashed line is the approximate northwesterly

edge of the floodplain. The coarse dotted lines, not to be confused with the

line of houses along Malibu Colony Drive, indicate, diagrammatically, lines of CPTs. A, B,

and C are locations of three borings

specially drilled for the UCLA study A

is very close to LB-1 The location of B

is uncertain LPS and CC indicate the

locations of the Lagoon project site and Malibu City Hall. Base: USGS 7.5-minute Malibu Beach quadrangle, ed. 1981, as modified.

Ignoring the

date error ranges - the averaged 6.5-foot section between the reported depths of

19.0 feet and 26.5 feet in boring B-9 was deposited during a period of about

1,350 years giving a depositional rate of about 1 foot per 208 years. Thus, it would have required 780 years to raise

the elevation of the floodplain at B-9 an average distance of 3.75 feet to the present

surface at elevation +23 feet msl. Because B-9 is located along the reach of the southwesterly creek

regime, this datum indicates that at least as late as 6,500 ybp the

southwesterly flow regime of Malibu Creek prevailed. Consequently, taking the

period of the Holocene to be 11,500 years, the incision of the meander neck that isolated the Serra

Retreat spur must have occurred within the past 5,000 years.

Comment

Neither the data from Bausch, et al. (op. cit.)

nor the cores for the UCLA study provides a sufficient basis

for the lithologic detail of Figure 3 That

the subsurface data are considered "consistent" by Ambrose and Orme (op. cit., p. 1-20) with the figure can

mean nothing more than that it depicts one of an infinite number of ways that

subsurface conditions might exist in the floodplain; in fact, it is simply an

artistic rendering Furthermore, the

data support neither the contact of "Fluvial gravels" vis-a-vis the overlying "Fluvial

sand," etc., nor their

horizontal and vertical distributions. In other words, whatever the GeoSoils logs of borings may show, those of

Bausch, et al. (op. cit., App. B) demonstrate simply that the mass called the

"Civic Center gravels" has a preponderance of sandy gravels recognizable

at certain locations below a depth of about 50 feet, but by no means do they demonstrate

the lateral or vertical lithologic continuity shown in Figure 2. Furthermore, although the depths of LB-1

through LB-6 ranged between 43.5 and 51.5 feet, only the log of LB-4, drilled

in the wetland of what was once "Malibu Lake"

reports significant organic material

Most likely, the transition of the

Civic Center gravel mass to the overlying "estuarine materials ... deposited

beginning approximately 15,000 years ago and continuing to about 2,000 years

ago..." as asserted by Bausch, et al.

(op. cit. , Sec. 5.1.4, p. 21), is

the result of a decreasing rate of sea-level rise during the later stage of the

Flandrian transgression Furthermore, disparate

occurrences of "estuarine" materials at depth lacking any evidence of

lateral continuity provide no basis whatsoever for postulating a lagoonal

condition over the floodplain during the Holocene epoch nor at any other time.

CONCLUSIONS

The available

subsurface data are insufficient to demonstrate that actual lagoonal conditions

persisted over most of the floodplain as late as 1,800 ybp during which

low-energy stream conditions would have to have prevailed. If that were true, it would mean that somehow,

since 1800 AD, the local area suddenly became the site of its present

high-energy stream depositional character to account for alluviums with upper

surfaces now in the range of +10 - +20 feet msl, well above the surface elevation

of any tidal lagoon postulated to have existed a mere 200 hundred years

previously Consequently, such a

postulate cannot be seriously considered. While an opinion of "... episodic wetlands throughout the

Holocene..." (op. cit., p. 1-19)

seems justified, the data do not support the idea of

an area-wide lagoon in the Malibu Creek floodplain at any time.

The

floodplain-wide lagoonal thesis of the UCLA study may have been presented simply

in support of the study's primary purpose which was to investigate existing

conditions in order to "... understand better the natural system and human

impacts on this system, and to develop strategies for the long-term management

of the lower watershed ..." (op. cit, p. iv) To that end, the UCLA study has

much to offer With regard to planning,

however, renderings such as Figures 2 and 3, per se, could have played a significant role in the minds of Malibu

Lagoon project planners as ostensibly confirming the idea of a lagoon at the

mouth of Malibu Creek suitable for restoration. To the extent that today's community of environmental shakers and movers

regard restoration as very important, if not the sine qua non, of project funding, it is a matter of significant concern

that the Malibu Lagoon project came to be implemented even though it has no

such antecedent character.

References

Ambrose, Richard F., and

Anthony R. Orme, 2000, Lower Malibu Creek and lagoon resource enhancement and

management: Univ. Calif. Los Angeles,

special study for California Coastal Conservancy.

Bausch, Doug, Gan Mukhodhyay,

and Eldon M. Garth, 1994, Report of geotechnical studies for planning purposes

in the Civic Center area, City of Malibu, California: Leighton and Assoc., Inc. rpt., Project No. 2920647-01 for Malibu

Village Civic Association, March 18.

Rindge,

Frederick Hastings, 1898, Happy Days in Southern California: The Riverside

Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and Los Angeles, California,

reprinted by KNI, Inc., Anaheim, CA, 1984.

Yerkes, R.F., and

R.H. Campbell, 1980, Geologic map of the east-central Santa Monica Mountains,

Los Angeles, County, California; U.S. Geol. Survey Misc. Inv. Series Map

I-1146

* * *

|

| |